Last week I tweeted:

“When I was confused about why America was not building nuclear and nothing I read gave a satisfactory explanation, I got a job at the regulator.

You can just learn things, even if the knowledge is locked away in a literal tower.”

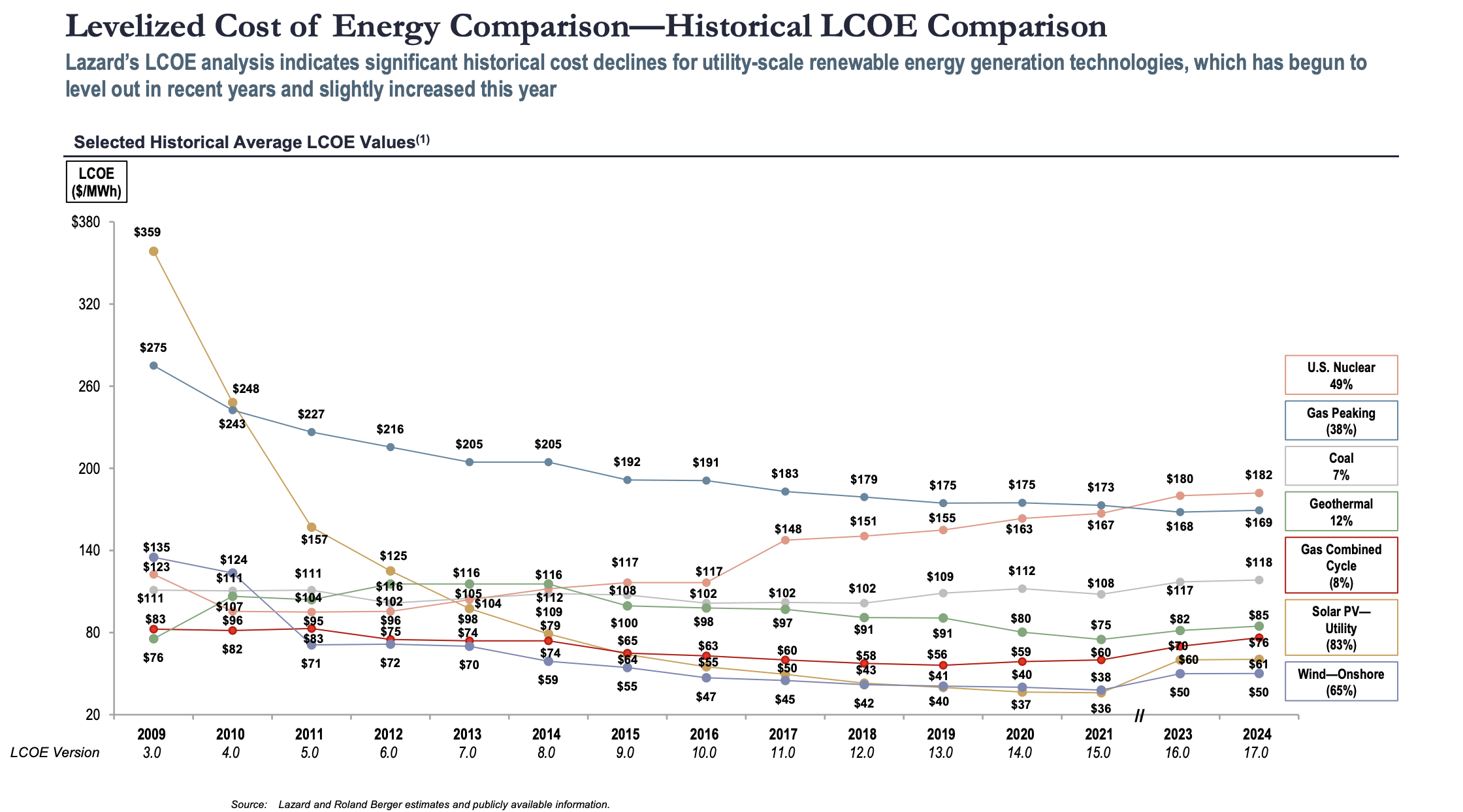

Simply put, American nuclear is too expensive. Much fuss has been made about the public misunderstanding and unpopularity of nuclear, but these are merely contributors to the prohibitive electricity prices it provides. Utilities don’t build them because they have cheaper options over shorter timelines.

LCOE = levelized cost of energy, or the average cost of generating each unit of electricity over a source’s entire lifespan.

Note: The increase in nuclear LCOE in recent years is due to the Vogtle project in Georgia, whose massive cost overruns highlight the primary faults in the American nuclear-industrial complex.

About 70% of the levelized cost of nuclear power is project financing. While this ratio is comparable to other sources with no-or-low fuel costs (like solar), the permitting process for nuclear is arduous and leads to long, unpredictable timelines. Banks dislike this uncertainty and raise interest rates. Once built, nuclear power plants produce electricity around the clock for over 60 years, and although such predictable cash flow would normally warrant low interest rates, the capital intensity and extended construction timelines frequently spiral out of control.

To build a nuclear power plant, you must obtain regulatory approval for your reactor design and site, and meet exacting requirements for materials and construction—standards that most heavy industries struggle to achieve without difficulty.

In the U.S., we have made almost every mistake in the book. We keep attempting to build new “modern” reactor designs, even though approval takes as long as designing the reactor itself. When a new design is finally built for the first time, mistakes are almost always made; due to strict requirements, these errors can cost billions of dollars and add years of delays. For example, at the Vogtle plant in Georgia—which came online last year—concrete was poured 3 inches off design specifications, forcing the construction crew to tear up approximately $2 billion worth of work and start over.

Data from China and historical U.S. experience suggest that once a national supply chain and construction team has successfully built the same reactor design more than 5 times, mistakes and delays virtually cease without any compromise in regulatory scrutiny. The U.S.’s last “fleet building” era occurred during Westinghouse’s golden age in the 1960s, ending with the disruptions caused by the 1979 Iranian revolution and global oil crisis.

The massive uncertainty around future energy prices shifted investors toward less capital-intensive options—such as natural gas—leading to the cancellation of almost all nuclear power plant contracts. This trend nearly bankrupted Westinghouse and General Electric’s nuclear arms and shifted the contractor economy from constructing new plants to upgrading existing ones for previously unnecessary “safety” reasons, a much easier alternative for raising quick capital in the wake of public concern following the 1979 Three Mile Island accident.

Reactor build sites must also remain compliant with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)—a law that, in short, mandates that any infrastructure project involving the federal government must fully assess its environmental impact to comply with other environmental regulations. A product of the Nixon administration, NEPA has done wonders for preventing environmental harm but can stymie projects regardless of their potential benefits. For instance, while the long-term environmental benefits of the offshore wind farm in Long Island Sound far outweigh the loss of a seagrass bed in New London Harbor, NEPA does not weigh these factors and delayed the project while its impact is evaluated. Nuclear energy, too, offers broad environmental benefits—it occupies little space, uses virtually no fuel, and produces no emissions. However, as projects grow more complex, NEPA reviews lengthen and open the door to an extensive public comment period, which is sometimes hijacked by pseudo-environmental interests. Federal regulators must “adequately address” all public comments, and while this system was designed in good faith, it is grossly abused in bad faith. NGOs opposed to nuclear power, as a rollover from the anti-war / anti-bomb era coordinate campaings to flood public comment periouds with junk, stalling the rulemaking process. Over multiple comment periods, this adds up and the costs ulitmately fall on those paying electric bills. While originally intended for public transparency and accountability, public comment periods across energy regulation have been hijecked by degrowther interest groups. Because comments can only slow the process down, they are the only ones who show up. As one regional planner put it, “The selection effects are mind-bogglingly bad.”

This is a fixable problem. Stay tuned for part 2.